El Tatio Geysers

Best things to do in El Tatio: experience the explosive power of the largest geyser field in the Southern Hemisphere with this travel guide.

One of the most interesting sites I’ve witnessed, El Tatio, is a volcanic geothermal field home to dozens of geysers.

Located in the Andes Mountains in northern Chile, El Tatio sits 55 miles from San Pedro de Atacama in an area that’s overwhelmingly dry and arid.

Tatio’s geysers spring up violently from deep within the earth, spraying boiling water and steam high up into the air or stay low, gurgling just above the surface.

Be sure to arrive early at the geysers to experience hot steam spewing into the chilly morning air as the sun rises behind the mountains.

Eager to see it all, our time in Chile focused on three regions: central, northern and southern, in that order. The two weeks were a major undertaking including eight flights, countless bus and taxi rides and even a ferry.

Our first destination was the capital city of Santiago to enjoy Chilean wine, world class cuisine and an undeniable art scene.

Next, we moved north to San Pedro de Atacama, the driest place on Earth. While in the Atacama Desert, we arranged a handful of incredible tours, including Chaxa Lagoon, Piedras Rojas and Altiplanic Lagoons for its pink flamingos, red rocks and blue lagoons, Andes Mountains to witness the El Tatio Geysers, northern Atacama to moonwalk at Valle de la Luna and Atacama Desert to stargaze like we meant it.

After the desert, we flew to the tip of Chile's southernmost Patagonia region and gateway to Antarctica, Punta Arenas.

Then, it was on to Torres del Paine, Chile’s Patagonia, with an exciting opportunity to witness Patagonia’s waterfalls, icebergs and glaciers.

And last but not least, our journey lead us to Castro on Chiloé Island, a land of myth and sea.

Best Things to Do in El Tatio

Set Eyes / On the northern geysers

Gaze / Awestruck at the Assassin Geyser

Breakfast / Alongside a marsh

Visit / Vado Río Putana & Flamingo Lagoons

Best Things to Do in El Tatio

Set Eyes on the Northern Geysers

With San Pedro de Atacama as home base and moving between two tour agencies in town, Turismo Gato Andino and Horizons, we filled our last day with three local tours. First up was El Tatio, then Valle de la Luna and finally the Atacama Desert for stargazing with an astronomer; it would be a long and adventurous day.

Bright (actually, dark) and early at 6 a.m. in the morning, Fabio, our guide, and Jose, our driver, arrived at our hotel for pickup. We’d be heading an hour and a half north to the El Tatio geysers. Nodding off until we arrived at the entrance, we had to open our sleepy eyes, run to the restroom and bundle up for the cold air that awaited us. Somewhere around 30°F, we’d layer on long socks, gloves, hats and thick jackets.

El Tatio is a geothermal field located in the Andes Mountains of northern Chile at 14,170 feet above sea level. It’s the largest geyser field in the Southern Hemisphere and the third largest in the world with only Yellowstone and Dolina Geizerov in Russia being larger. Together with Sol de Mañana, a region just east of El Tatio in Bolivia with fumaroles, hot springs and mud pools, El Tatio is the highest-altitude geyser field in the world.

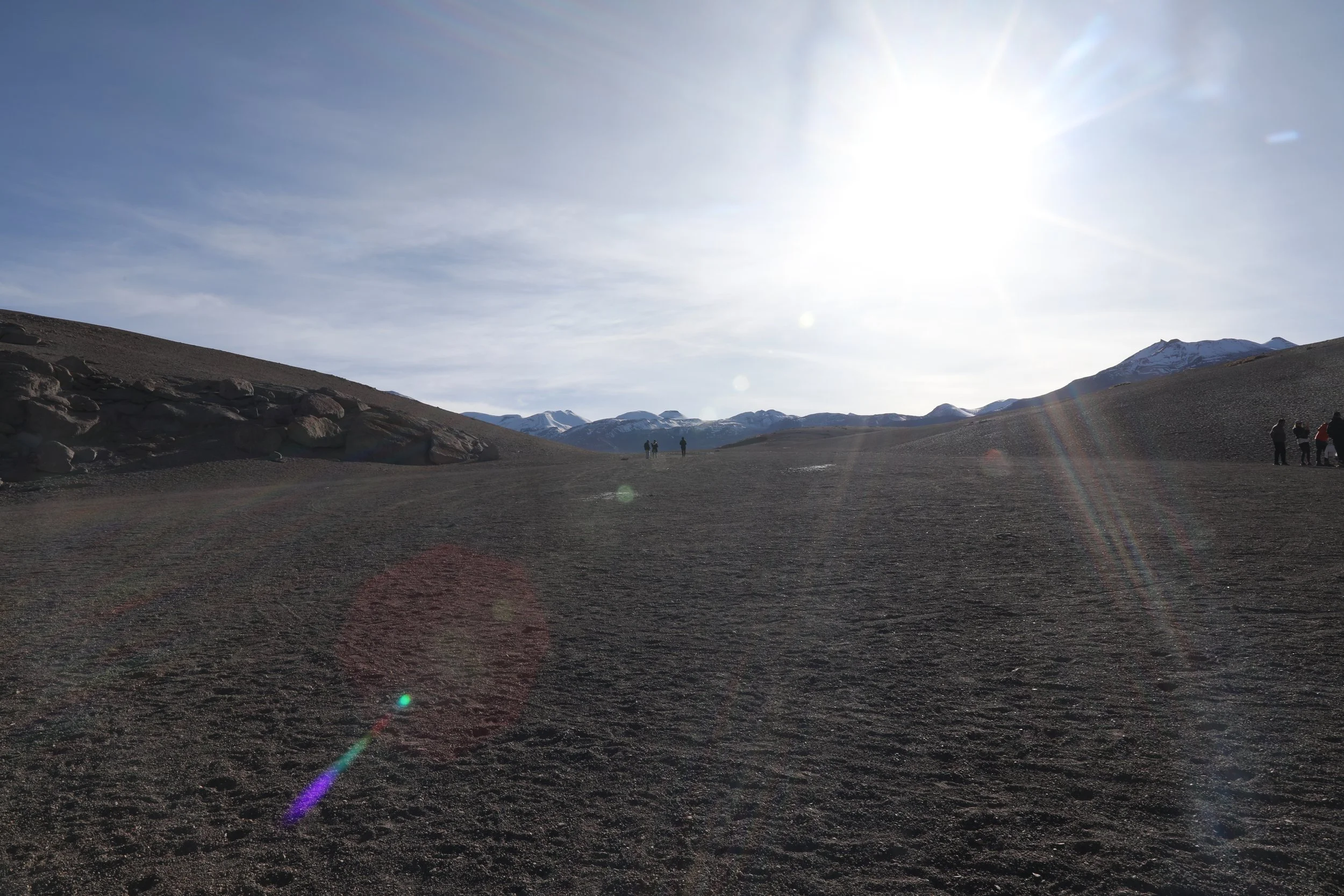

Immediately after stepping through the official entrance, there were geysers in all directions and small pathways marked with stones to keep visitors on course and safe. Puffy white steam clouds pushed out of the earth and contrasted against the dark shadows of the mountain range in the distance; I was shocked the geysers were so active.

The geothermal field covers an area of 12 square miles at elevations ranging between 13,800 and 15,100 feet and is defined by fumaroles, or openings in the Earth's surface that release volcanic gases and steam. They can appear as holes, cracks or fissures and emit a variety of gases, including water vapor, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, hydrogen chloride and hydrogen sulfide.

Stronger activity lies within three distinct areas covering only four square miles and includes geysers, hot springs, boiling water fountains, mud pots, mud volcanoes and sinter terraces, along with chimneys of extinct geysers. One of the three areas sits within a valley, the second is on a flat surface and the third sits along the back of the Rio Salado.

The term “tatio” comes from the Kunza language and means ‘to appear’, ‘oven’ and has also been translated as ‘grandfather’ or ‘burnt’. The geyser field is known as the Copacoya geysers, after a nearby mountain. The earliest mention of geysers in the region dates to the late 19th century.

El Tatio lies at the western foot of a series of stratovolcanoes, a conical volcano built up by several layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra, fragmental material, which runs along the border between Chile and Bolivia. This string of volcanoes is part of the Central Volcanic Zone, one of many volcanic belts in the Andes, and of the Altiplano-Puna volcanic complex. It’s a system of large calderas potentially responsible for eruptions from one to 10 million years ago that may be the source of heat for the El Tatio geothermal system.

With about 8% of the world's geysers, El Tatio is ringed by volcanoes and fed by over 80 gurgling geysers and one hundred gassy fumaroles, or vents. The geothermal field is made up of geysers, hot springs and their associated sinter deposits. Sinters are deposits of silica precipitated by hot waters discharged at the vents of hot springs and geysers.

Most sinters are precipitated as non-crystalline opal but they change to quartz during diagenesis, the physical and chemical changes that occur during the conversion of sediment to sedimentary rock. The hot springs eventually form the Rio Salado, a major tributary of the Rio Loa.

Opal is the most important component of sinter related to hot springs, with halite, sylvite and realgar less common. During its precipitation, opal forms tiny spheres and glassy deposits that gather on the environment’s wet surfaces.

Depending on the season, the hot springs yield water at temperatures reaching the local boiling point. The water is rich in minerals, particularly sodium chloride and silica, as well as other compounds and elements like antimony, rubidium, strontium, bromine, magnesium, cesium and lithium.

Some of the minerals are toxic, especially arsenic which pollutes several waters in the region. Arsenic concentrations at El Tatio can reach some of the highest levels found in hot springs in the world and are linked to local health concerns.

The vents at El Tatio are sites of populations of extremophile microorganisms. Extremophile microorganisms are those able to live in extreme environments, such as extreme temperature, pressure, radiation, salinity or pH level. They form mats, multi-layered sheets of microorganisms, mainly bacteria, within the hot springs and cover the solid surfaces. In other areas, microorganisms form floating rafts of bubbly mats, with layered and conical textures in colors of orange and olive green.

Steam vents are best seen early in the morning between 5:30 a.m. and 7:30 a.m., when the steam columns are highly visible in the dim light of the rising sun. The temperatures of the steam typically range between 118.9–196.9 °F, so it’s extremely important to be cautious when in their presence, particularly because their spewing can be unpredictable.

Much of the water that is released by the hot springs seems to originate as precipitation that enters the ground east and southeast of El Tatio. The source of the heat for the region appears to be one or more of several sources: the Laguna Colorada caldera, the El Tatio volcanic group, the Cerro Guacha and Pastos Grandes calderas or the Altiplano-Puna Magma Body. Water is able to move under the surface due to the permeability of the volcanic material. As it moves underground, it gains heat and minerals and loses steam through evaporation.

Local precipitation has had little influence on the hot springs and is not mixed into its waters. Incredibly, it takes anywhere from 15 to 60 years for water to move from precipitation into the springs, with ¾ of the heat carried by steam.

The climate in the region is extremely dry with only 1.7 inches of precipitation each year, mostly occurring between December and March. It’s also very windy which affects the hot springs, causing higher evaporation and pushing geyser growth in certain directions as material is guided by the wind. Additionally, extreme temperature variations between day and night are the norm, reaching freezing temperatures and highs near 72 °F.

About 100,000 tourists visit El Tatio each year, amounting to more than 400 daily. It’s an attraction with important economic benefits to the region and is administered by the local Atacameño population as part of a wider trend of cooperations between native communities and heritage sites in the region. Other than seeing the geysers, visitors can bathe in the hot water, admire the landscape and visit the surrounding Atacameño villages.

It is, however, very important that guests are careful in geothermal areas such as El Tatio. Exposure of hot gases and water can result in injuries, and both sudden eruptions of geysers and fountains and fragile ground above vents and boiling water, hidden beneath thin covers of solid ground, increase risk. At the site, pathways are marked with small stones, so guests are not led into any dangerous zones, while rings circle geysers limiting how close visitors can get.

It’s also important to note that the region sits at a high altitude and can lead to altitude sickness. And the cold dry climate can cause harm, making it necessary to seriously bundle up, wear sunscreen and drink water often. In fact, the area is so extreme that it’s been studied as a prototype for the early Earth and possible past life on Mars.

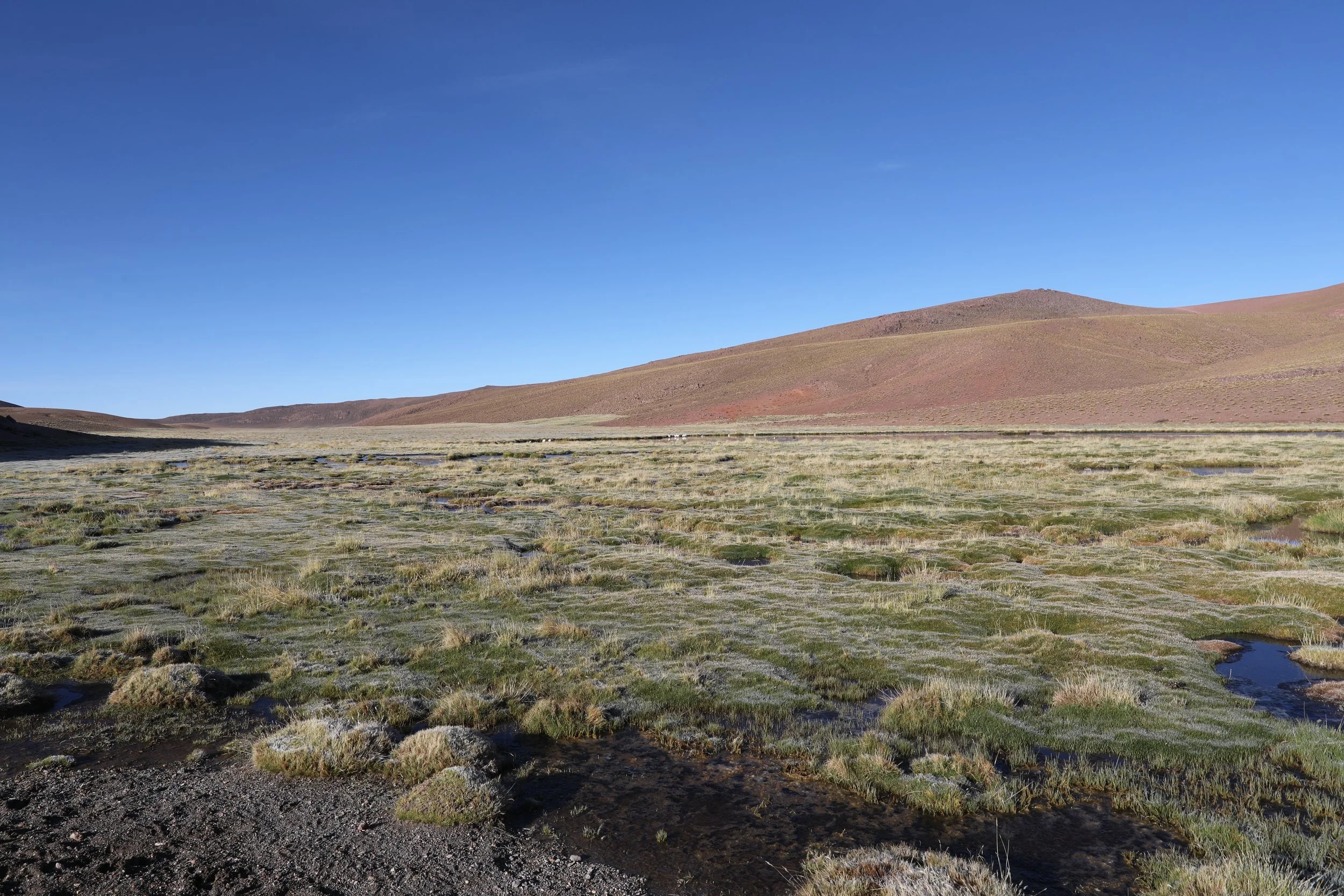

As far as the landscape, the region is a dry grassland, classified as Central Andean dry puna. Close to 90 plant species have been found at El Tatio and the surrounding area, while animals include chinchillas, viscachas, llamas and the vicuña. In the upper geyser basin, vegetation has been known to grow within thermal areas, such as thermal marshes, along with species of snail and frog.

After some time, it was challenging to keep warm in the frigid weather. My fingers had frozen over and I opted to use a small blanket as a cape.

Round and round we moved, through the geyser field. The geysers gave off a small amount of heat if you stood close enough but the hot water, steam and chemicals prevented one from getting too close.

Muddy pathways lead from one geyser to the next and some were more entertaining than others.

It was possible to see the various minerals that cause color variations on the surface of the geyser field. They seemed to form layers of crust and foamy bubbles that looked like a painting of beautiful watercolors.

And certain vantage points offered perspective on how large the geyser field was; it felt massive, like an oversized football field.

At one point our guide, Fabio, gathered us around and knelt to the ground, drawing diagrams explaining the geysers. He told us to get close to the ground and touch its surface; it was warm and steaming ever so slightly.

Fabio was very animated and passionate and knowledgeable about the geysers, as he explained what they are and how they’re formed. He explained, it’s not a geyser unless is has a hill around it which is formed by the minerals. Flat steam vents are young and bigger ones with cone shapes are older.

The formation of geysers depends upon the amount of water and minerals. If there’s a lot of both it will formed quickly. Some geysers stream and steam continuously, while others are sporadic. And some seem to have a tight schedule. A specific geyser sprays for seven minutes on and then five minutes off. This is because some geysers have chambers below that need to fill up and once they do, they have enough pressure to spurt out. Sometimes a single chamber below may lead to multiple openings.

As the sun rose and the gorgeous colors of pink, tangerine and gold subsided, our group moved on from the northern geysers.

Gaze Awestruck at the Assassin Geyser

The Assassin is the single largest geyser in El Tatio and south of the others we’d just seen. It was given this name by tourists, as it’s the most dangerous geyser in the region.

Before the geyser was marked off with barriers, several tourists had gotten too close and fallen in causing chemical burns within a few seconds. In 2016, after this happened to a woman, her husband sued to make conditions safer. Today, the geyser is closed off making it impossible to get too close.

The approach made it evident just how big the Assassin truly was. Its steam cloud pushed up into the air nearly 100 feet and formed large billowing clouds around its source. The clouds were so large, it was tough to locate the geyser and confirm if water was spraying upward.

Once close enough, you could see the shadowy “hole” and the geyser’s massive size. It looked as if a full size car could fit right inside.

As the hot subterranean water builds up pressure, it’s released through cracks in the earth’s crust. The boiling water can reach temperatures of 185°F, while steam vents are produced from the contrast with the cold ambient temperature and can reach heights of 32 feet.

Up close, the steam billowed from the geyser in thick white clouds so dense you couldn’t see though to the other side. If you looked close enough, you were able to see bubbling boiling hot water at its center, spewing out of control.

Nearby, there used to be a warm pool, similar to a hot spring. However, people would often breathe in too much gas, leave the pool and get too cold and then pass out, so it was closed recently.

After several minutes observing the Assassin, our group was ready to move on with our day. We’d be grabbing breakfast and making a few more stops along the way back into town.

The geysers were an unbelievable experience, one I’d never had before and will treasure for some time.

With one last look and the crowds dissipating, I said my goodbyes to the geyser.

It looked as if it were something out of a storybook, or something I’d seen years back in The Road Runner Show.

Breakfast Alongside a Marsh

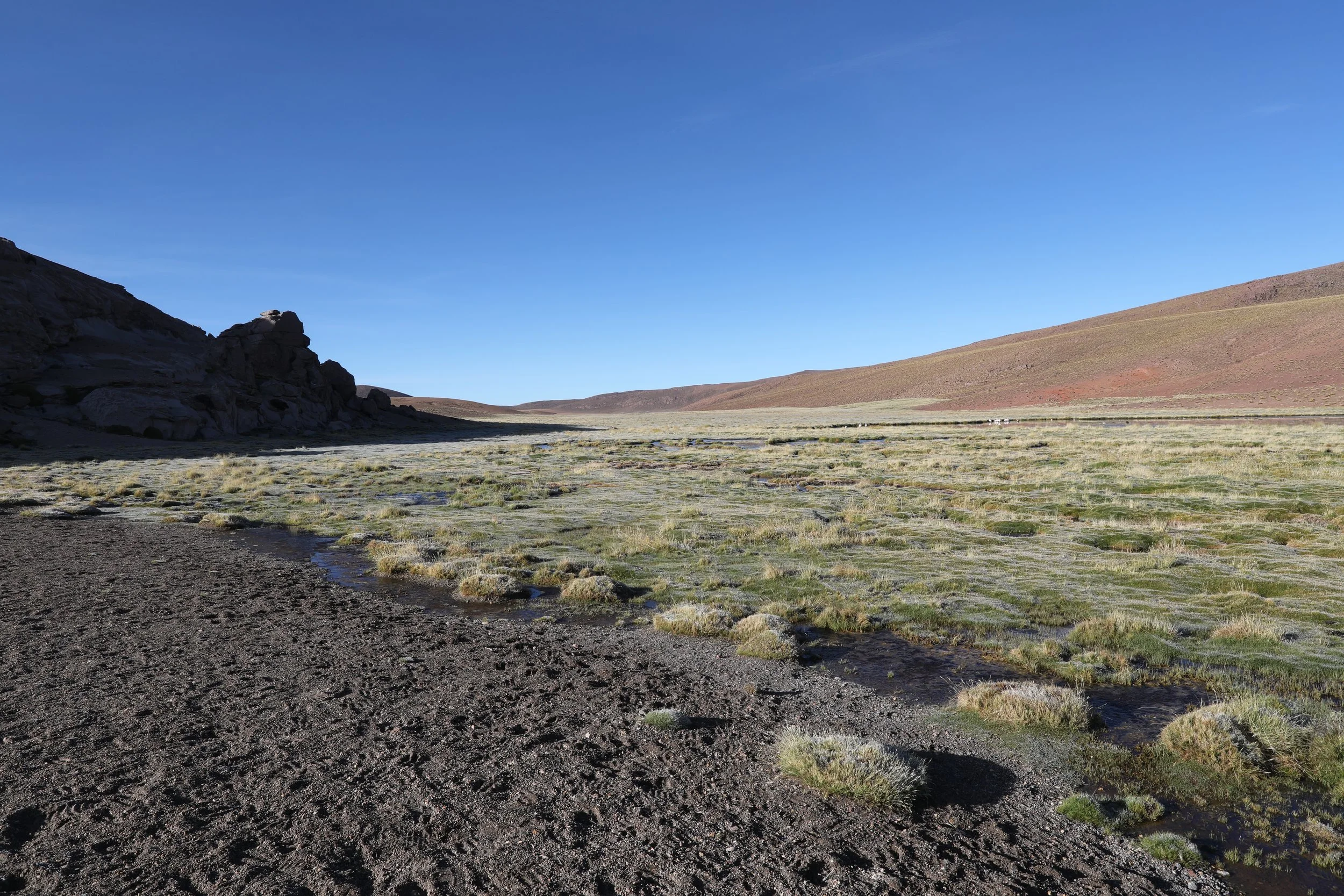

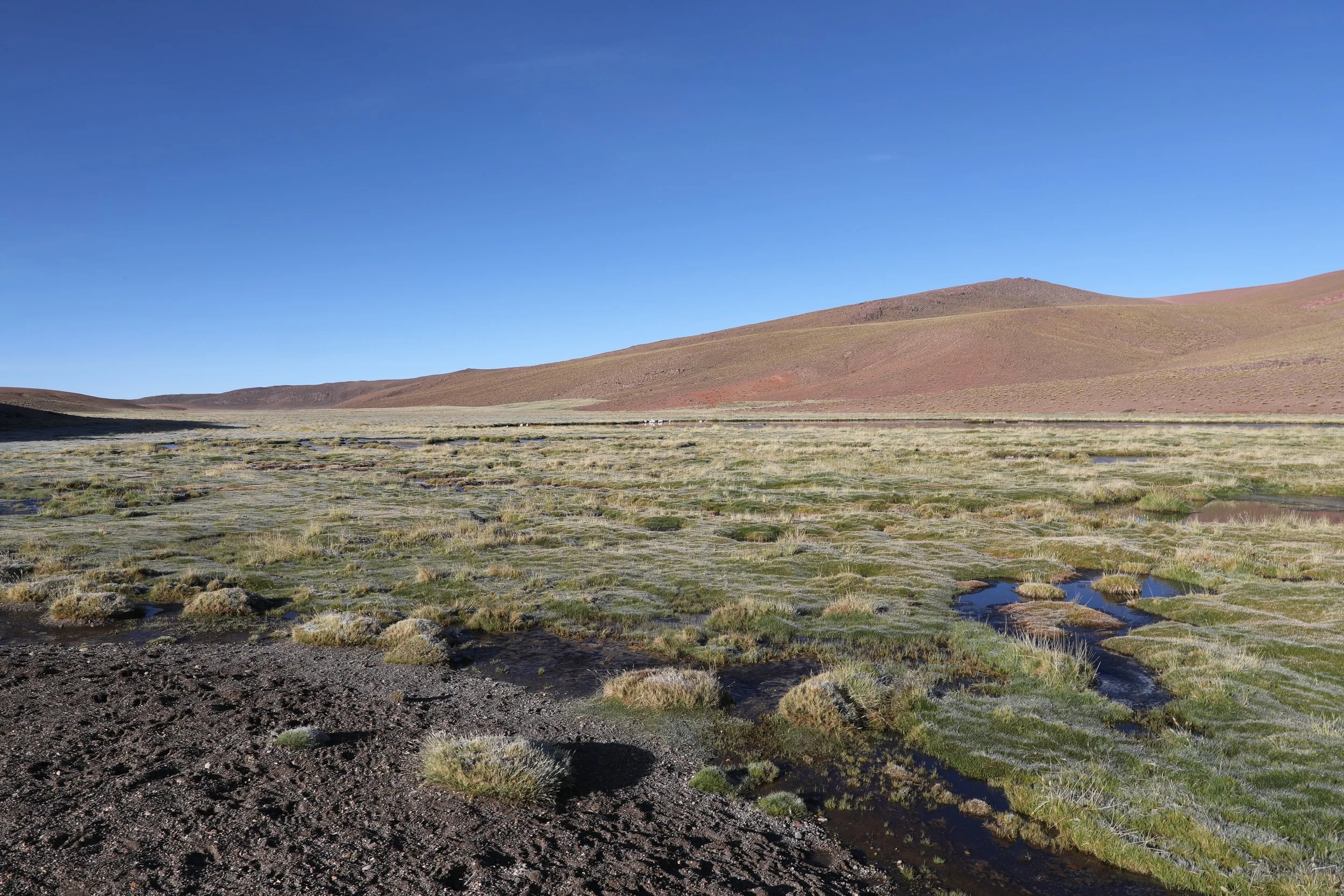

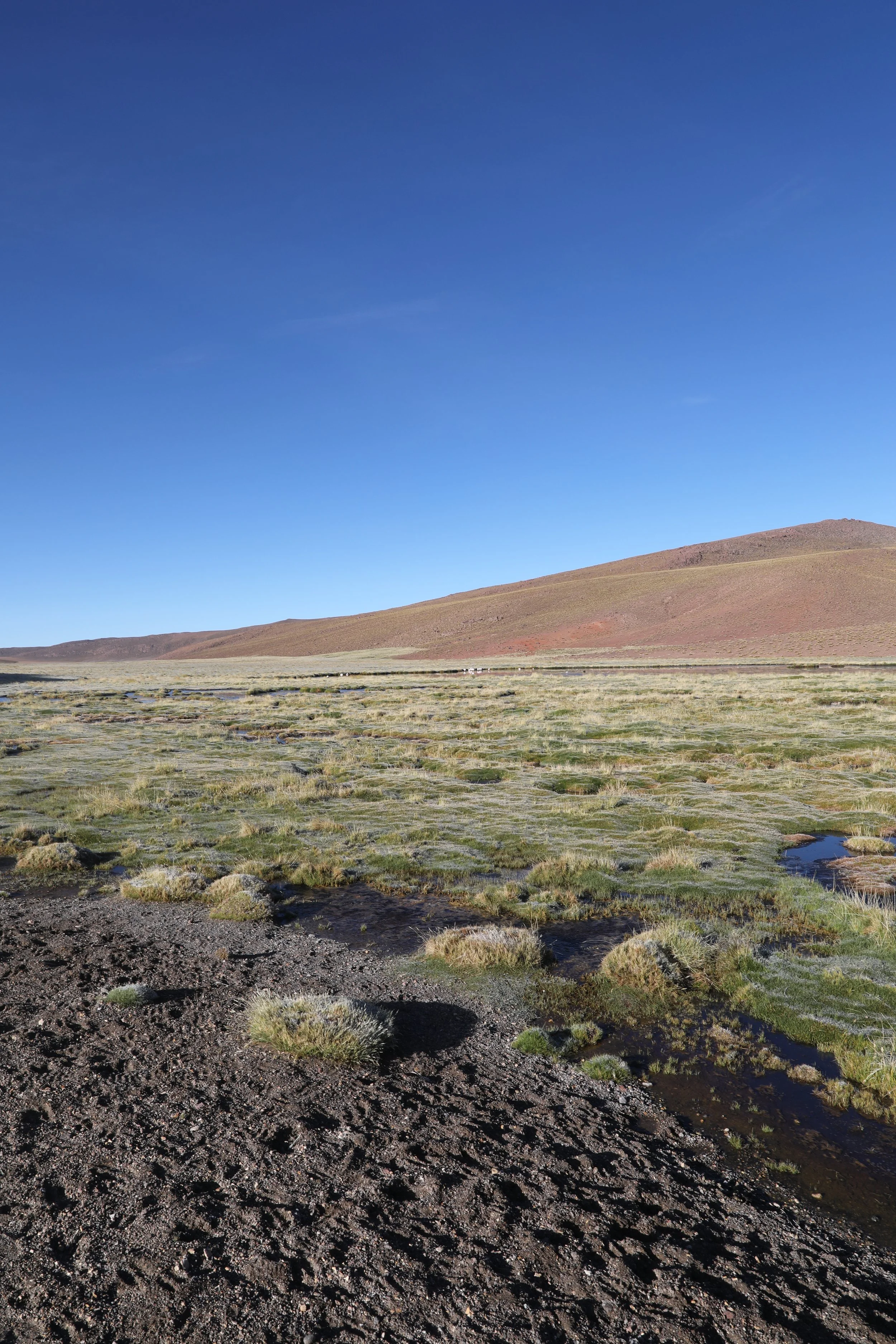

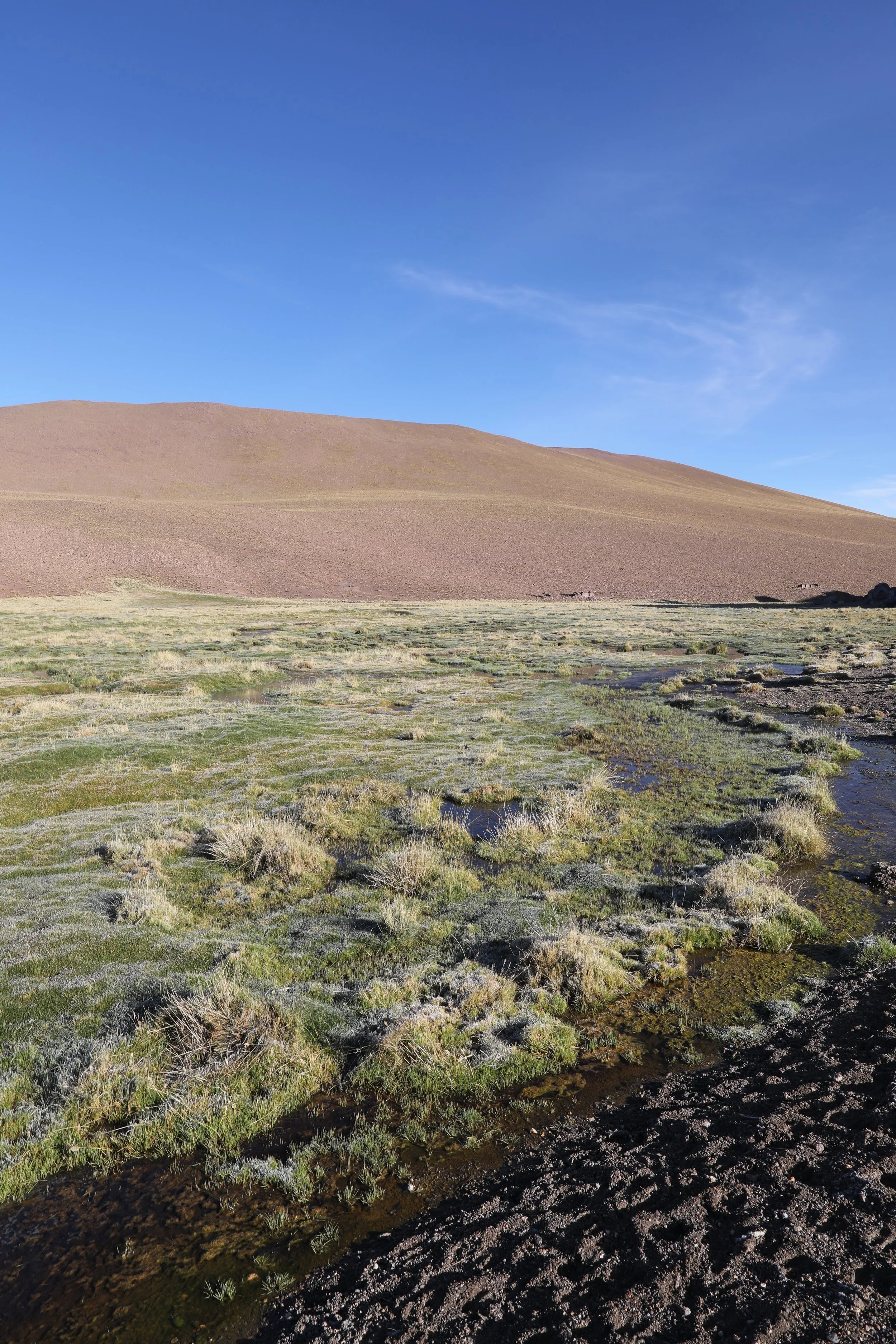

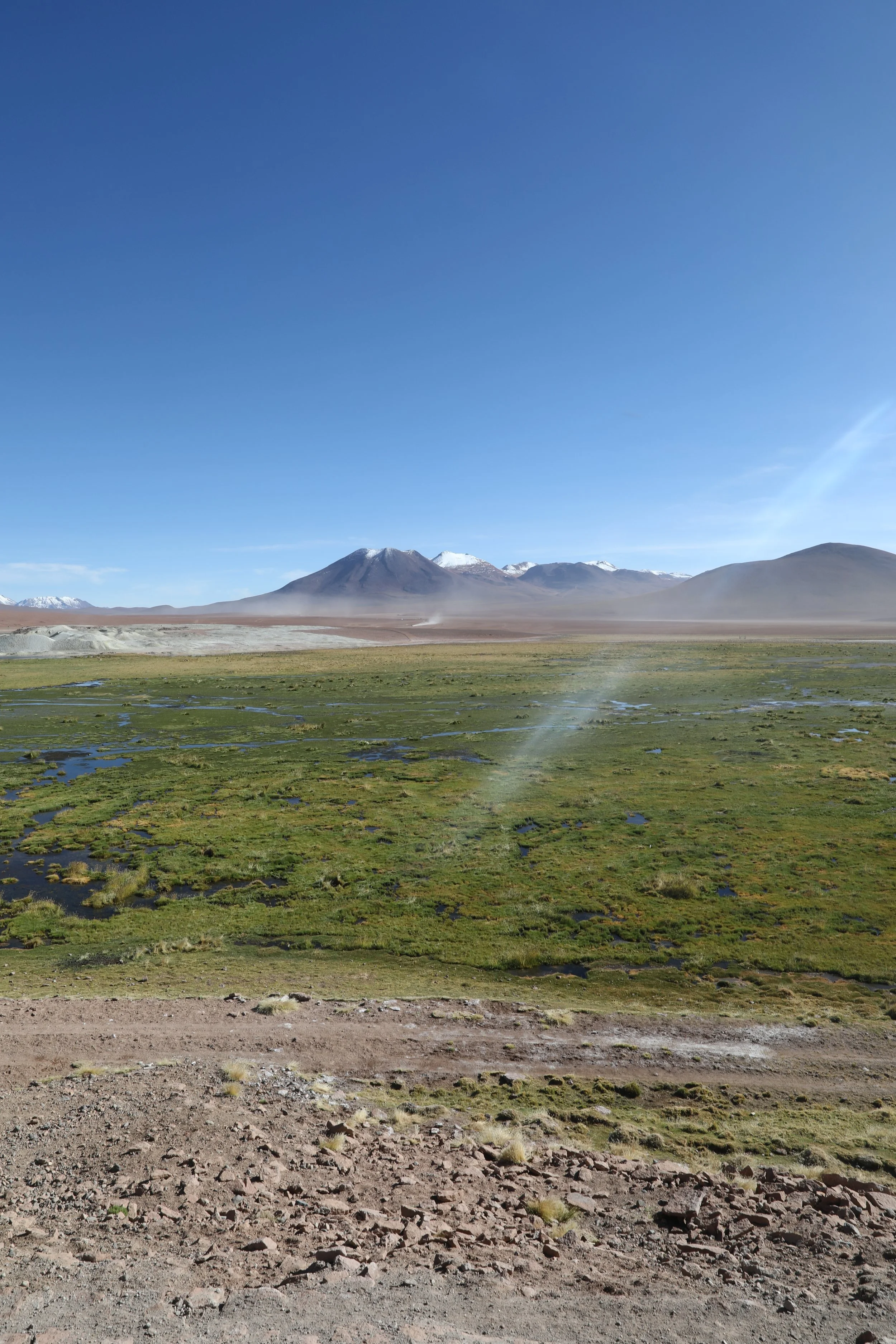

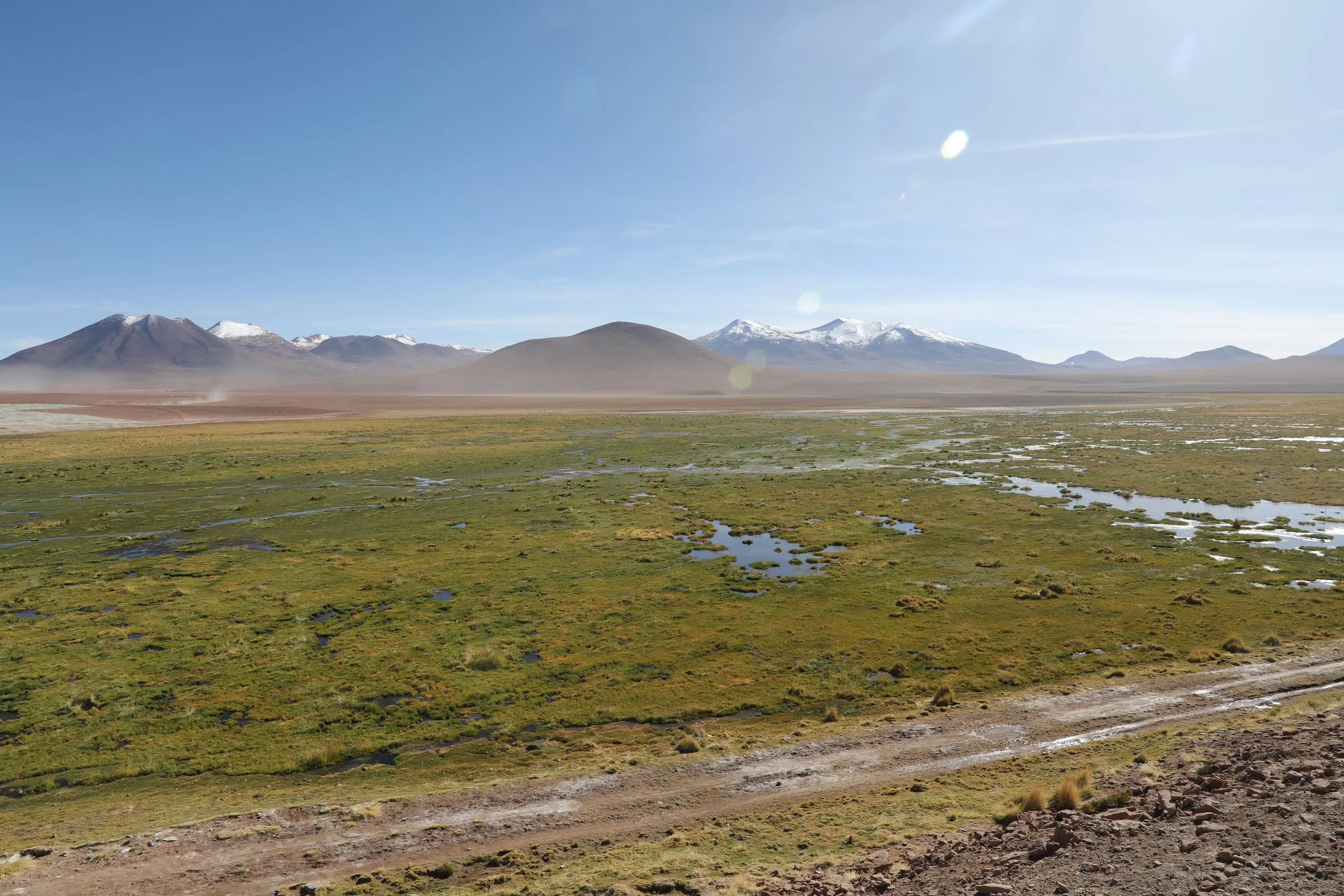

After an amazing morning at El Tatio, our group climbed back into the van to warm up and headed to breakfast at a nearby marsh. We drove down into a sandy bank and parked.

The wetland was a gorgeous setting to relax and unwind. While we waited for our guide and driver to prepare a small feast, we roamed around the area, spotting vicuña and other wildlife like flamingos and small birds.

Some were standing in the water, feeding on grasses, while others came in and out of the site from above, curious about what we were up to. The sand was covered in animal tracks, those looking for a drink of water or to snack on some tasty grass.

Finally, the sun began to warm the chilly landscape. The morning had turned out to be a beautiful one.

And I wanted nothing more than to warm up in its rays, taking in the scenery and clear blue sky.

After a few minutes of preparation, our meal was ready. We were served French bread, ham, cheese, scrambled eggs and fruit with hot coffee and tea.

Simple but fresh and delicious, the ingredients were perfect to make a few breakfast sandwiches and dig in. Yes, please!

Our group sat quietly in a small circle and enjoyed out breakfast, then, got back to exploring the surrounding area while our leaders cleaned up.

We spotted a vicuña getting an early morning snack in the marsh and watched on as it moved about, chomping on the tough green grass.

Ready, we loaded into the van and got comfortable until we reached our next destination.

Visit Vado Río Putana & Flamingo Lagoons

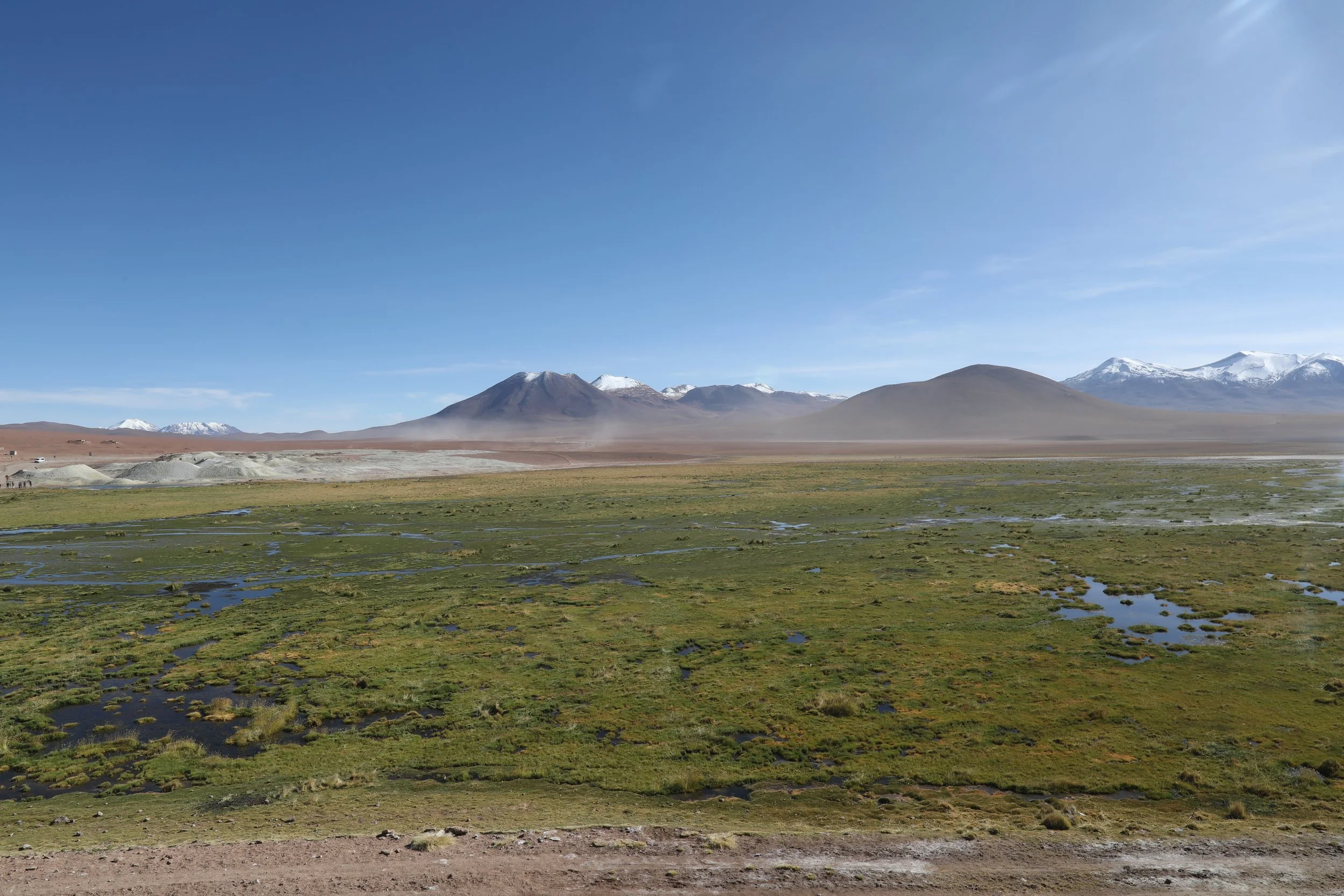

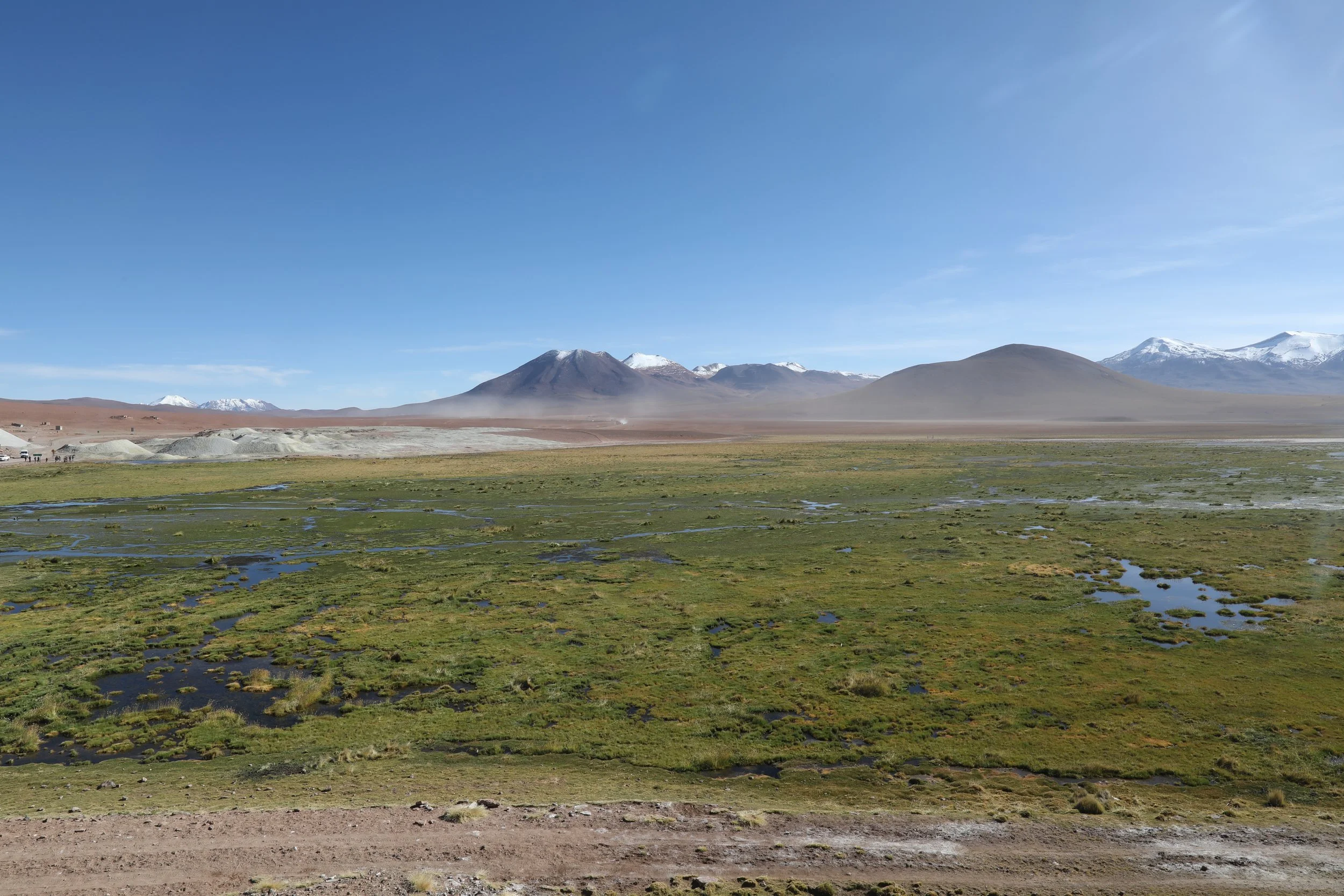

Our next stop was Mirador Putana overlooking Vado Río Putana, or Putana River and lagoon. The river, originating with the name Ojos de Agua del Putana, is a natural water stream that originates in the Putana volcano in the Andes Mountain range. Flowing mostly in a southernly direction until Putana River joins Juana River and becomes Rio Grande, the springs can be seen on the northern slope of Putana volcano. From there they flow westward 13 miles, receiving tributaries, one of which begins in Bolivia at the foot of Volcanes and Agüita Brava hills. Other important tributaries come from the north and the Tocorpuri hills until they form the Putana River itself.

Surrounded by volcanoes, the lagoon was a brilliant green. The viewpoint, Mirador Putana, offers a stunning vantage point facing Vulcão Putana, also known as Jorqencal or Machuca. Putana Volcano is a stratovolcano on the border between Chile and Bolivia. It lies north northeast of Cerro Colorado about four miles south of the Cerros de Tocorpuri complex and displays powerful fumarolic activity from which smoke and gases arise, particularly from the main crater.

In in the 1980’s, the area also used to be a location to mine sulfur but it has since closed.

Nearby, Flamingo Lagoon provides views of another lagoon where flamingos gather to mate and gorge on shrimp. This time, the water was so deep that the flamingoes floated on its surface, resembling swans. They were bobbing underwater with their little bums and feet sticking up, in search of food.

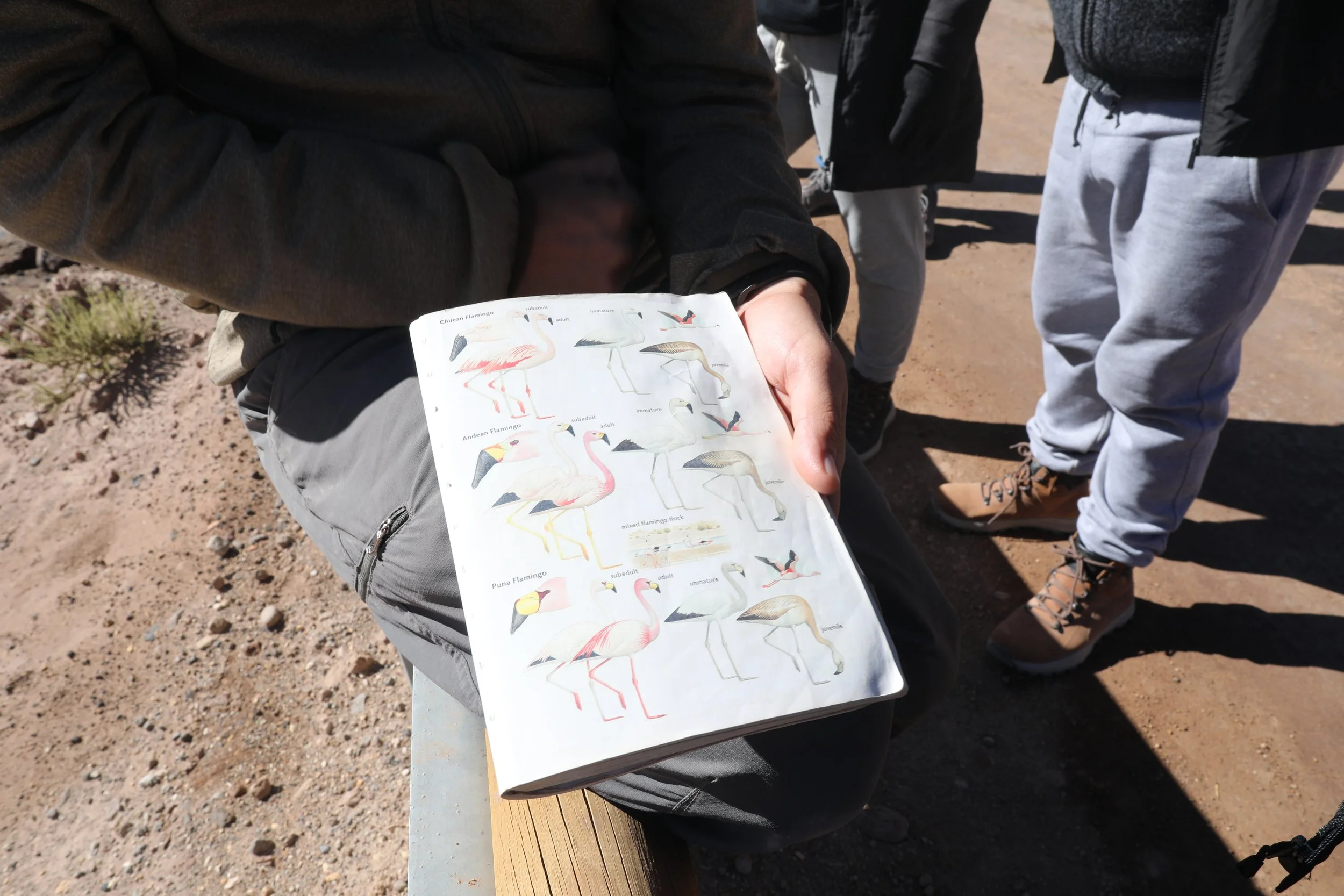

Others flew overhead, which was fascinating to witness. Then, we learned about the various types of flamingos present in Chile: the Chilean flamingo, the Andean flamingo and the Puna flamingo, all with distinct colorings and characteristics.

Once we’d seen all we could, it was time to head back into town, arriving at our hotel around 11 a.m. with just enough time to prepare for our next tour of the day. Overall, this was a really special tour, one that we enjoyed so much; the geysers were fascinating.